Dick Allen and the year of magical hitting

Sports Illustrated

I really don't care that Dick Allen wasn’t voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame before he died. I don’t care if he ever gets into the Hall of Fame at all.

The folks who vote for such things can’t take 1972 away from me. For me, it was the best year to be a White Sox fan, even better than the World Series 33 years later.

Allen, all by himself, was magical, and I was still young enough to be thrilled by magic, ready to believe that the world was infused with enchanted beings who could easily rise above the common herd, even the common herd of major league baseball players, who are not common at all.

The championship season was an unexpected thrill, but by then, I was an adult with a child getting ready to start school. In the heat of the pennant race, I was disconnected from the drama in Chicago as I trudged through the Louisiana heat in the wake of a devastating hurricane.

During the playoffs, I listened to a Sox-Boston game on the radio on the way home from covering a night meeting, satisfied with my level of involvement. I pulled over just in time to see El Duque destroy the Red Sox in a tavern full of Cubs fans.

Sports had generally become less compelling with time. I was driving a cab in 1984 when I went into a liquor store-tavern to pick up a fare. While I was looking around for him, I peered through a gap in some shelves and saw a television set with a Bulls game on the screen. I saw a shooting guard who looked like he could almost fly.

It was very cool to see Michael Jordan for the first time. It would be cool to watch him do amazing things for years. But I couldn’t help but regard 1984 and 2005 as real life compared to the enchantment of 1972, when my less-cluttered mind was more open to the possibility of magical events.

And the head Houdini was Allen.

Opening Day he hit a loud homer. Of course. The White Sox lost anyway. Of course. Winning had not been a thing for the South Side players for a while.

They would learn.

Allen didn’t look mortal. He hit balls so hard with his ridiculous, 2 1/2-pound bat that there were times when an outfielder would get a bead on a line drive, plant his feet, and see the ball veer away from him at the last moment.

Twice in one game, Allen drives got past talented Twins outfielder Bobby Darwin, and Allen easily scored inside-the-park homers. Darwin maintained that Allen’s power caused balls to fly with no spin, giving them a unique high-speed knuckleball-like effect.

Allen was always entertaining, even just standing still, leading off from first base. He did that a lot in 1972, because he led the league in walks. He stole 19 bases in 1972, which is pretty impressive for a player who led the league in homers (37) and RBIs (113).

One of the White Sox’ uniform styles was baby blue. The only player who looked good in it was Allen. He looked good in everything.

It was comical to watch the Comiskey Park concourses just before Allen was due at bat. The doors of all the washrooms would burst open, and fans would rush back to the stands, often still zipping up their flies.

No one wanted to miss what might happen.

One day in August, Allen homered to center when Harry Caray was broadcasting from behind a beer cup-strewn table in the “batter’s eye” alongside the left-field bleachers. The ball nearly hit him, almost 500 feet away from home plate.

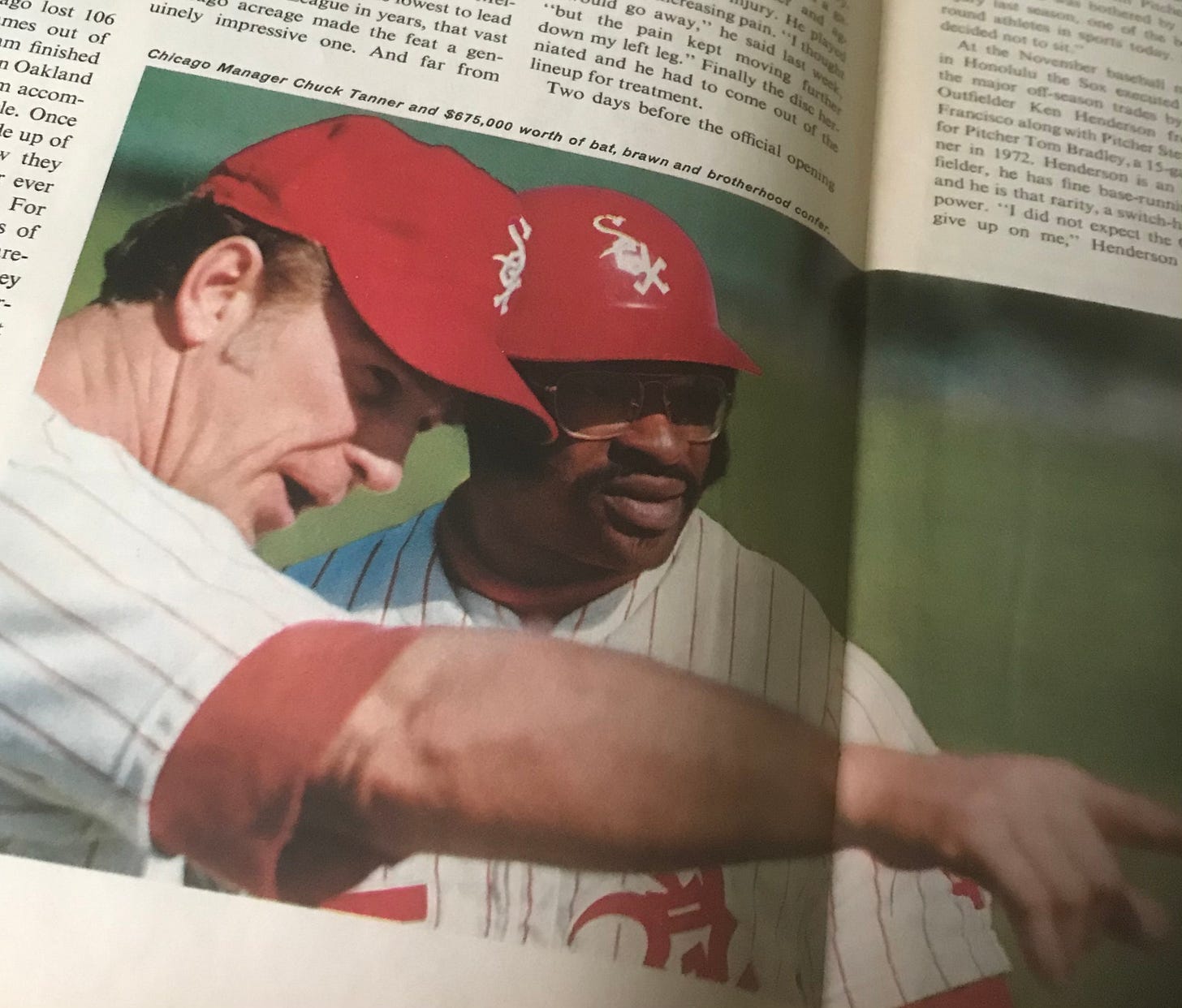

Famously, Allen was given the second game of a Bat Day doubleheader off. With the Sox trailing the Yankees in the ninth, manager Chuck Tanner called him in the clubhouse and told him to grab a bat. He jumped into a uniform, dumping his chili dog all over his jersey. He ripped it off and grabbed another one, ran up to the field and hit a line-drive walk-off homer to left field. Sweep.

The White Sox finished in second place, 5 1/2 games back of Oakland. I wasn’t disappointed. They were 20 games over .500, and this was a team that hadn’t won more than it lost for five years.

The three top starting pitchers won 60 games in a strike-shortened 154-game season. That was more than the whole team won two years before.

It had been the year that we had moved in the middle of a school year from the neighborhood we’d lived in for 10 years, the year I caught encephalitis, the year of Peace is at Hand and Nixon’s landslide and the Munich Olympic massacre.

But in my memory, those moments of 1972 will always be tempered by magic on the South Side.

Sign up to get Irv Leavitt’s “Honest Context” free in your inbox by clicking on the subscribe button.