Returning to the Land of the Living

All year, I've spent less time with a keyboard than with ambulances, MRIs, wheelchairs, nurses and hallucinations

I woke up at 4 a.m. and looked out the window. The moon, full and bright-white, mottled with grey lunar seas and plains, hung in the sky high above the tops of buildings.

Never has the moon seemed more welcome. It was the first time I’d seen it this year, which has progressed from winter to spring to summer without much notice on my part.

This year, my world has been almost entirely separated from nature. I asked a friend to bring me a cicada, so years from now I can say I saw one.

I live in a space in which the only life is my own, except for people who come and go, concerned mainly with the effort to preserve that life.

I have a handful of maladies that could kill me or come close. But I’m probably the right person to have them.

No kids at home or needy relatives. No regular job, so there’s little fretting about undone work. I’m calm.

Sometimes I do have feet of clay, however. I try to forgive myself at those times, and also for my past weaknesses. I recall them more readily, as relative solitude has afforded me so much opportunity to remember.

Thanks for reading this, my return to the written word, to the exercise of a happy habit I’ve neglected for the longest time in decades. I hope I can still do it.

If you think so, I’ll do some more.

One of my excuses for not writing was the considerable time I spent semi-conscious, and my numerous adventures in delusion and hallucination. While it’s usually fun to read about such experiences, it’s probably unwise to write about them while they’re actually happening.

I occasionally shook the hoary hand of death, but I am currently very much alive. And before the snow flies again, I expect to reenter the outside world, which has not been my place of residence since Jan. 23.

That was the day my daughter, visiting from Minnesota, called 911. I had planned to go to a doctor’s appointment, but couldn’t get up off the bedroom floor. I had hoped to scoot down the stairs on my butt, but I couldn’t even get to the door this time.

Incidents like that had been occurring, off and on, for months, perhaps due to relapses of multiple sclerosis. I repeatedly found myself crawling from room to room. Sometimes I slept on the floor. I have a nice Saatva bed, but it’s too high to mount when you can’t stand up.

Symptoms of MS started in the summer of 2019, but weren’t diagnosed until late October 2020, by a sharp guy named Paul Pritikanta.

The previous delay was partly due to the difficulty of getting help from doctors during the first year of COVID-19, and partly because I felt guilty about pressing for medical attention when sicker people seemed to be dying for lack of it. But mostly, it was the failure of neurologists to think outside the box. I was over 60, and most people get MS when they’re under 40.

Immediately upon diagnosis, I was found to have bladder cancer, too, when I peed the color of Coca-Cola. That sometimes comes along with MS. The bladder cancer was on the run by 2022, after regular treatments of chemo pumped through my urethra by Roohollah Sharifi, and his scraping away of evil cells.

My MS symptoms included leg weakness, fatigue, and constipation. Still do. I’m working on all of that.

MS involves deterioration of the myelin in the lining of the spine and parts of the brain. It can result in a vast variety of deficits, a few, or none at all. It can interfere with almost anything controlled by nerves.

My favorite writer about MS, Sweden’s Frederic Andersson, wrote that when asked how he feels, he may reply, “I'm weird, thanks. How are you?"

In mid-January, I signed a lease on an apartment in an elevator building. Before I could pack, Chicago Fire Department paramedics took me to Swedish Hospital.

They slid me off a stretcher and onto a bed that I wouldn’t leave for about three weeks, except to go to a different bed. My right leg wasn’t just weak anymore; it lay there like a pipe. I was tired, the kind of tired pulling a couple of all-nighters in a row gets you.

Maybe three.

I slept away most days, flat on my back as if in a coma or dead drunk.

While I slept, my daughter and some friends packed up my stuff for the movers.

I’d apparently wake up once in a while and tell my kid and a friend to stop stealing my stuff. I was told about this later, but didn’t remember.

I’m still working on amends.

A day or two after I arrived at the hospital, a doctor told me I had lymphoma, a kind of blood cancer, which had ravaged my adrenal glands. They didn’t treat it because they couldn’t quite discern what type. There are lots.

But they, prompted by the friendly insurance company, sent me to a nearby facility to rehabilitate, anyway. The cancer could be dealt with on an outpatient basis.

A few weeks later, Wesley Place rehab loaded me, sick and delusional, into a private ambulance to go to a hospital. I don’t remember that. But I heard later that I was in the ambulance for 2½ hours. Apparently, I was driven from hospital to hospital in search of one that would take a patient who had gone septic.

Northwestern Memorial said Yes. Doctors, nurses and certified nursing assistants saved my life. It took a while.

At least at first, I was a little blithe about the situation, but I’m told I shouldn’t have been. Later on, my primary care physician, who'd been following my case via digital reports, said, “I hate to tell you this, but I didn’t think you were going to survive.”

One of the reasons was the sepsis, which is always scary even if you don’t have it as bad or as long as I did.

Another is that my blood pressure occasionally ran away to hide, once at Swedish and once at Northwestern.

“All you guys running in here, it’s like one of those TV doctor shows,” I remarked. Dawn to dusk, there were never fewer than a dozen people in my ICU room when it happened at Northwestern. Some of them seemed very concerned, but I got a kick out of all the attention.

Some other days in the ICU were different, because the sepsis had gotten into my brain.

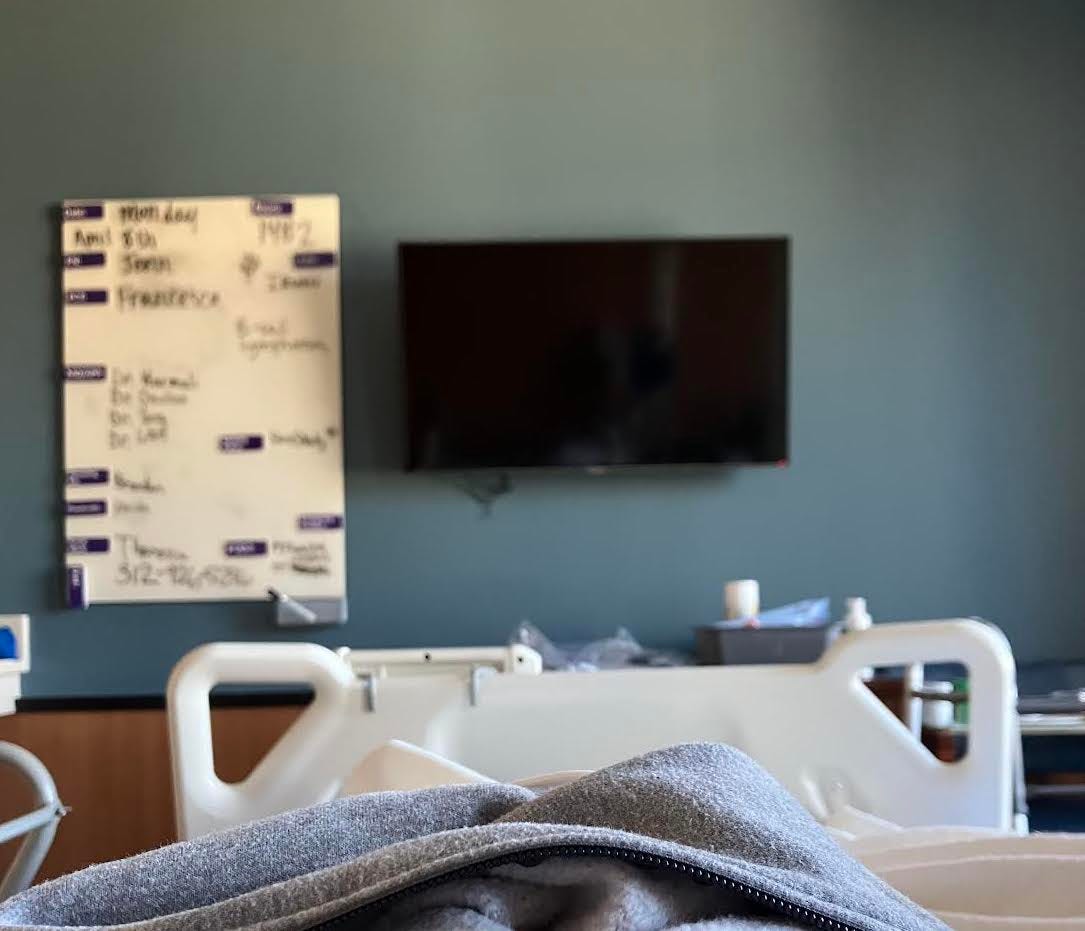

One day, I looked at the big whiteboard where my various caregivers and their assignments were listed, and saw extra notes, like the hometowns of the various people.

“That's new,” I said to a nurse. He looked at the board but didn’t respond. I shut my eyes and looked again. Still there.

Day after day, new messages appeared on the board. Dumb jokes. Nonsense names.

“Did a kid somewhere maybe hack the whiteboard?” I read the odd verbiage aloud.

“No,” the nurse said. “You’re the only one who sees that.”

A day or two later, the whiteboard was shimmering, as usual, but this time, the shimmer slid off onto my bed’s blanket and turned it every color of the rainbow. The colors moved around as the bed undulated. I enjoyed that for a while.

Wait a second, I thought. Beds don’t change colors. Go away, colorful bed.

The bed was not cowed. “Nuts to you. This is my truth.”

But after a while, the colors left, and with them, the imaginative whiteboard remarks.

I had lots of other delusions and hallucinations, however. A nurse and I traveled to Mexico and teamed up in his hometown’s annual boat dock-building competition.

And he wasn’t even Mexican.

I think it was at this point that I started getting a little antipsychotic Seroquel pill once in a while.

I was convinced that the earpieces of my horn-rimmed computer glasses had sheared off and melted into the shape of Mercury’s wings, both on the same side of my head.

The only certified nursing assistant who didn’t seem to like me plotted against me. She refused to keep me clean, and, to mock me, hung dozens of 3-D decorations on the walls. Some of them were trowels, perhaps to represent the equipment to dig my next home.

I don’t remember what the other decorations consisted of, other than they were made of molded plastic in the purple and white of Northwestern University.

I didn’t report her, which was good, because it’s not likely that any of it happened. She may not have even existed.

I woke up one morning to find several pieces of used medical equipment in the palm of my right hand and on the bedsheet. I had apparently disassembled the PICC line, an intravenous device that leads from ports hanging on the arm to tubes running through the arm toward the heart.

I spent one evening on a stretcher in a big room with several scary people who may not have actually been there. I ate what appeared to be a non-existent sandwich. Where I actually was, or what I actually ate, I’ve no idea.

I don’t know whether I had my eyes closed when I was imagining this. But I definitely dreamed about being strapped onto a hallway stretcher being gleefully experimented on by medical students. It was vivid.

Real life was occasionally exciting, too. A couple of weeks into my stay at Northwestern, tests revealed I had B-cell lymphoma. NU oncologist Reem Karmali scrawled “START CHEMO” across the test result.

A great doctor, skilled in her craft and quick to answer my stupid questions.

I guess I was septic and mostly sleeping for about two months. When that was over, my legs and arms had lost much of their muscle from not moving. I’d lost 60 pounds.

The right leg had the get-up-and-go of a fallen tree. I could move the equally skinny left leg but it couldn’t come close to holding me up by itself.

One day, I had a thought. I could move two toes on the right foot. So I did.

I wiggled those toes for three hours that night while I reread “The World of Jimmy Breslin.”

Breslin was the best newspaper columnist of the late 20th century. Sorry, ghost of Mike Royko.

The wiggling loosened the other three toes. Then the ball of the foot got free. After that, I was able to waggle the foot left and right. In a week, I could lift my heel an inch off the bed.

Northwestern Memorial physical therapists tried to get me walking, but I still couldn’t stand up. They attached me to a “Sara Stedy” device, which yanked me up from a sitting position. With two people’s help, I could walk a step to a chair.

Arjo Sara Stedy Stand-Assist Manual Patient Standing Aid

It was hard to sit on it because sometime before arriving at Northwestern, I had developed a bedsore on the top of my butt.

Bedsores hurt, and make everything harder. They need regular attention, and for patients who can’t move much, might last the rest of their lives. If they do, I suspect those lives are shorter.

But I had frequent “wound care” at Northwestern, and later at Warren Barr Gold Coast, where I have done rehab since arriving there in April. The bedsore is now closed up, and promises to be completely healed soon.

The lymphoma is in remission, thanks largely to Karmali and the imaginative and diligent work of U of I Hospital’s Paul Rubinstein. I had my last chemo Aug. 8, but didn’t opt for the traditional celebratory ringing of the bell.

Red Devil chemotherapy (Doxorubicin).

I don’t feel like celebrating yet.

I’m still not walking much, even with a walker and two therapists, ranging from a high of 150 feet down to 55 feet on bad days. Still struggling with the gut. It appears the bladder cancer has gained on me. Care for that had to wait until the lymphoma chemo was done. We’ll know soon.

This essay has been a long slog through my last seven months of incarceration. Thanks for sticking with it. I tried to make it entertaining because I have found it that way. Life is interesting no matter where it’s lived.

Many people who have had bad sepsis later have return of the hallucinations, plus other mental problems, fears and pain. I’ve had very little of that. When I saw those things coming, I was usually able to head them off quickly.

My life has aspects that many people might find demeaning or even horrible. I don’t: I’m chill. So the right guy is in Room 810 of Warren Barr.

As Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak allegedly told President-elect FDR upon taking a bullet meant for him in 1933, “I’m glad it was me instead of you.”

I have confidence in my dignity, and gratitude for those who help me hold fast to it. Many of those people work at Northwestern and Warren Barr. Some work at Swedish and Wesley, too.

I deeply appreciate the help medical people and friends have given me. They’re all wonderful.

At least 15 people have visited me in various rooms (about 20 rooms in five facilities). I usually lead the league in visitors.

Among them, Dale Duda, Elizabeth Austin, Gail Schechter, Ian Watt, Lynne Stiefel, and my daughter Megan were probably responsible for me getting this far. The rest, including Barb Bell, Bruce Elder, Cathy Backer, Dan Dorfman, Gerry Labetz, Joe Cyganowski, John Fay, Jo Peer-Haas, Juliet Ziak, Kathy Catrambone, Lee and Nancy Goodman, Mark Wukas, Miriam Anita Joseph, Rick Kambic, Susan Klein Bagdade and Todd Shields, have saved my sanity.

A dozen more friends have gabbed with me on the phone. Calls are like transfusions of the mind.

The real heroes of hospitals, rehabs and nursing homes are the nurses and nursing assistants. Many helped me in ways beyond the call of duty. With grace.

I won’t forget them for the rest of my life. It will likely be longer because of them.

Irv you can still write! Do it often.

For a while I wasn't sure if I was reading Irv Leavitt or William Burroughs. "Naked Sepsis" was fascinating, but I don't envy you the research. As usual, I found your writing terrific.