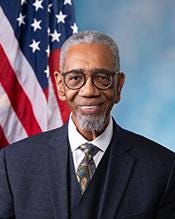

In 1975, future U.S. Congressman Bobby Rush told future journalist Irv Leavitt he didn’t know what he was talking about.

Rush was frustrated, I felt at the time, because I had kicked his ass in an impromptu debate about affirmative action, in a room full of my fellow students of the Chicago Circle Campus of the University of Illinois.

But frustration aside, he was right. I didn’t know what I was talking about.

I didn’t know in the same way that the U.S. Supreme Court majority’s justices didn’t know what they were talking about in the decisions they handed down today, striking down affirmative action in higher education (and probably some other areas of American life).

It was easy to argue my 1975 point, and the point made by Chief Justice John Roberts and the conservative wing of the Court today. Too easy. When your opinion seems irrefutable, it’s often because you’re kidding yourself.

My core argument had been: Affirmative action is not just about Black people being given extra points to help them win a job or an education. When somebody wins because they’re given a leg up, that also creates an instant loser who misses out through no fault of their own.

That’s true, but it’s not the whole story. We’ve made it harder for some people to make it in America, and if we don’t put a thumb on the scale, it’ll take forever for them to catch up.

Rush, then 29, had tried to explain that to me. I was 19.

When we met, he had been active in the civil rights movement, first as a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and then as co-founder of Illinois’ Black Panthers. He had recently quit the Panthers, because, he said, they had become too thuggish.

He lectured us about the Afro-American Patrolmens’ League, which had recently won a court case. It gave Black applicants for Chicago police jobs extra points, winning them positions they would not otherwise get.

I agreed with him that there should be more Black cops in Chicago, because an 85% White force was not a good thing for the city. But I disagreed with a system that purposely favored less-qualified applicants.

I maintained that the Supreme Court was committed to making decisions that were not only creating significant precedents, but also to be fair to the parties in the cases they were judging. Individuals should be treated equitably, including police department hopefuls who scored highest on their own hook.

Another point I made was that until recently, Ivy League law schools had quotas restricting the number of Jews admitted. That may have given a better chance to Gentile applicants, but it wasn’t fair to Jews like me.

There weren’t going to be too many Circle students heading for Harvard Law School. But still.

As long as my opinions of the last century remain attractive to six justices of today’s Court, there’s no way they would have blessed affirmative action. They see it as unnecessary, 160 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

In his concurring opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas referred sarcastically to fellow Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s view of affirmative action: “we are all inexorably trapped in a fundamentally racist society, with the original sin of slavery and the historical subjugation of Black Americans still determining our lives today.”

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson

Despite his attitude, the playing field’s still uneven. It would be great for affirmative action to have outlived its usefulness, but it hasn’t yet. One can see the evidence all over.

Several years ago, I joined a suburban North Shore group of education activists on a tour of Fenger High School, a nearly all-Black Chicago school on the far South Side. Most of the visitors were from the New Trier High School district, which was then funded with over $18,000 per student. The South Side kids got less than $12,000, and it showed.

I remember a Fenger computer class where the students were getting no individual help. Several looked lost. New Trier would have had at least one teaching aide roaming the classroom to make sure that didn’t happen. A Fenger administrator looked like she might cry when I suggested an aide there.

Some machining of admission policies at Harvard University – one of the schools involved in the Court’s decisions – would probably be necessary for more than a handful of Blacks to make it in. Nationally, Blacks score about 16% lower on ACT and SAT tests. Harvard usually has enough applicants with near-perfect scores to fill almost all its slots.

College is not only a place where young people get educational opportunities. It’s a chance to learn more about their fellow Americans. When I transferred to Illinois’ campus at Champaign-Urbana, I met my first farmers. Some of them met their first Jews and Blacks.

Just a few years after the Afro-American Patrolmens’ League case, 40 percent of Chicago police officers were black, more than twice as many as before. There are more Hispanics and women now, too. We want that.

A lot of the White guys who really wanted to be police officers made it, too. One in three current Chicago cops is White.

Discrimination in home financing left Blacks out of the post-World War II housing boom. The generational wealth that accrued through home ownership left out Blacks. Current White home ownership: 73%. Black: 44%.

Black college education tends to even things out.

We learned recently that real estate tycoon Harlan Crow bought a house for his pal Thomas’ mother to live in, free. Everybody can’t be that lucky.

This is a hard one for me. In my view, hundreds of years of subjugation for people of color required a public policy to help structure a more even playing field. But the system was flawed when it discriminated against better qualified ... many of which were fortunate to have beemtter foundational education. Investment per student is a huge issue. No pun intended, but it isn't a black and white issue. So complex because racism and bias is with us, perhaps forever because we are a flawed race ... human race, that is.

No affirmative action policy operates to prefer a less-qualified candidate - they operate to select a previously-disadvantaged between equally-qualified candidates. To say otherwise is simply racism rearing its ugly head.